In the article, What is a Powerful Place? we describe a number of factors—underground energy lines, orientation, construction ratios, etc.—that contribute to making a place powerful. In How To Experience A Powerful Place, we suggest ways to set your intention and consciously attune to a sacred site. In this article series, Types of Powerful Places Part 1 and 2, we focus on different kinds of powerful places—including mountains, islands, holy wells, trees, stones, and temples.

Trees and Forests

Trees provide humans with fruits and nuts, with fuel, with wood for boats, shelter, furniture, weapons, and coffins. But trees are much more than objects for human use. Trees are vital to the wellbeing of the planet, helping to maintain the stability of the climate. They “inhale” carbon dioxide and “exhale” much-needed oxygen into the environment. They hold the soil in place and exchange nutrients with it. They provide home and haven for animals, insects, and birds.

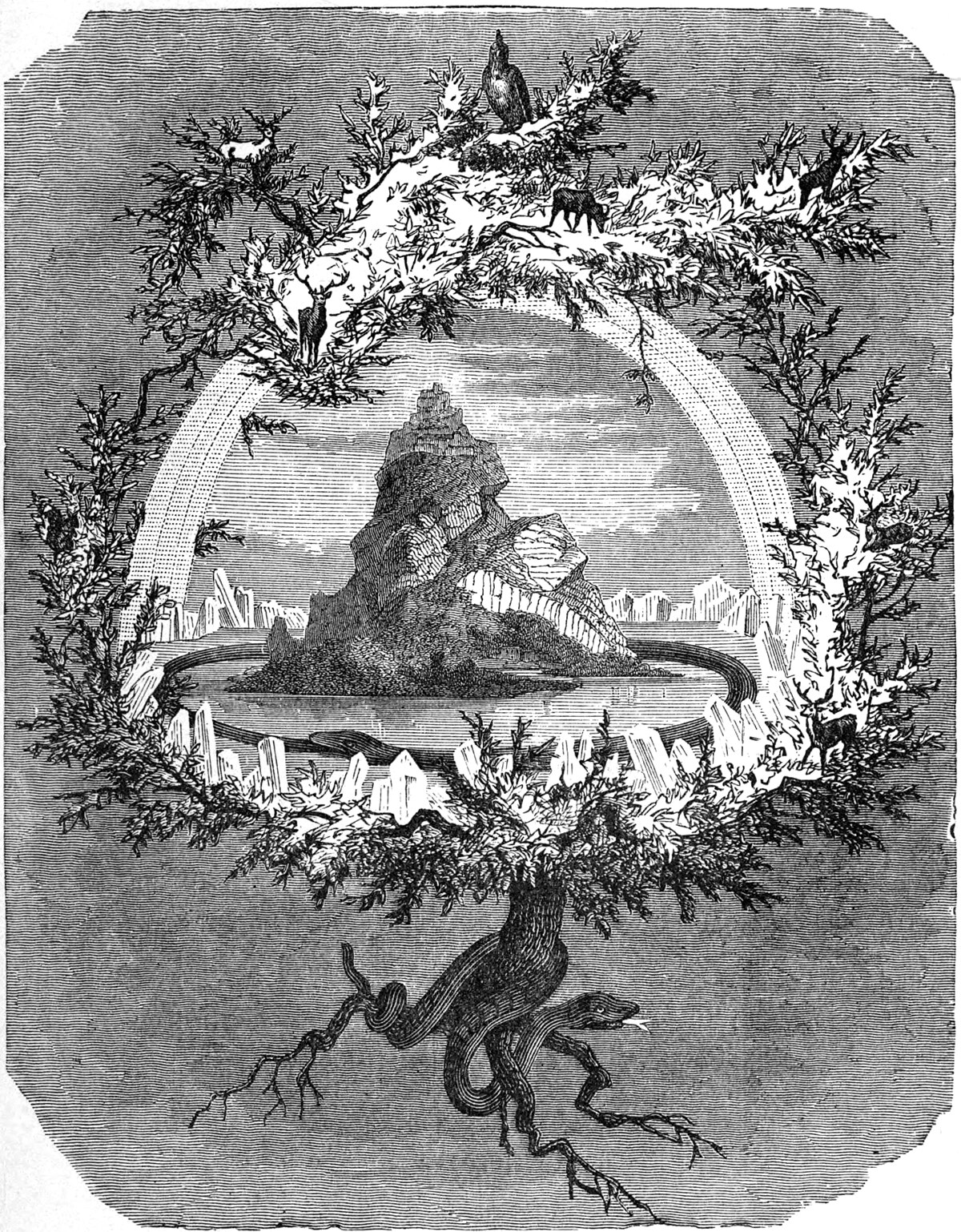

Symbolically, a tree is an axis mundi (a world axis), uniting the Underworld, this world, and the heavens. Different trees have different mythic associations. Yggdrasil, for example, is the ancient ash tree that Norse mythology describes as an immense “world tree,” complete with dragons entwining in its roots. One of the masterful columns in Rosslyn Chapel, Scotland, is thought to be a representation of this tree. Siberian shamans climbed the birch tree, using it to symbolize their ability to access other realms.

In Wales, ancient yews—some are even 2,000 or even 3,000 years old—are found encircling what were Neolithic sacred sites but are now Christian churchyards. Yew trees were sacred to the Celts, who associated the tree with healing, magic, communicating with the ancestors, death, and rebirth. In Ireland, isolated thorn trees are often called fairy trees, and folk tradition warns against disturbing them in any way. The oak tree has been considered sacred by many cultures, perhaps because of its size, longevity, and edible acorns. The oak is called the “King of the Trees,” and oak groves were associated with Druid worship.

To enter into a forest is to go from civilization to wilderness, to enter into a place where we rediscover our relationship with the elemental powers of Nature. On our pilgrimages on the Camino de Santiago in Spain and on the Way of Saint James (Chemin de St-Jacques) in France, we have walked on trails that pass through a number of forests. Although these were not as wild as the primeval Forest of Brocéliande in Brittany, or as evocative as the moss-shrouded trees in the Fairy Glen, Isle of Skye, Scotland, we found that walking all day through a forest is a consciousness-altering experience. The air you breathe is different, as are the sounds. What lies just beyond sight, hidden in the thick undergrowth? What is it that you hear, scampering across a tree branch?

Spend time with an ancient tree, such as the 500-year-old “Oak of the Damp Lands” in the Forest of Brocéliande, or the 3,000-year-old yew tree outside of St. Michael’s Church, Discoed, Wales. Take time to observe the tree from a distance. Introduce yourself. Ask permission to draw closer and enter the tree’s energy field slowly and consciously. The life-energy (aura) of a large old tree is vast, expanding far beyond the limits of its branches. See what you feel as you draw nearer. Do you identify changes in the energy around you? Listen carefully, and see what wisdom this ancient being is willing to divulge.

Stones

Stone is enduring, eternal—or at least closer to ageless than frail human flesh. Meditate on a stone and eons of geological time unfold before you. Perhaps part of the allure of megaliths is contact with what seems eternal. This contact is also with a part of ourselves, for we, too, are composed of minerals, of the dust of stars that coalesced into our planet Earth.

But there’s more to our attraction to megaliths than “like” recognizing “like.” Pay attention to the different megaliths in a stone circle or alignment, and you will realize that different stones have their own energies, their own “personalities.” Some have a masculine feel, other a feminine sensibility. Sometimes this relates to their shape (tall and pointed vs. wide or triangular, as at Avebury, England), but sometimes not.

Some stones appear to resemble birds or animals, or to have faces. Perhaps we are anthropomorphizing the stones, seeing meaningful shapes in the random wear patterns of millennia, but perhaps not. Perhaps the stones were selected precisely because of their evocative appearances.

The choice of stones for megalithic sites was often determined by what was easily available. However, on some occasions, great effort was undertaken to transport specific kinds of stones great distances. Recent research at Stonehenge suggests that some of the Preseli Bluestones were transported from 240 miles away from a recently identified quarry on Carn Menyn, a mountain in the Preseli Hills of Pembrokeshire, in southwest Wales. The unusual spotted dolerite stones have large white spots; they also turn blue when wet. And some of them “ring” when struck with a mallet. They may have been worth transporting because of they were believed to have special healing properties.

The reconstructed façade of Newgrange Burial Mound, Ireland, is faced with white quartz interspersed with dark, egg-shaped granite stones. The stones were transported from different regions; the quartz came from the Wicklow Mountains to the south. One can imagine the sunlight glinting off the white quartz, making it shine like a beacon. The glittering quartz remains cool to the touch, while the darker granite absorbs the sun’s rays.

Notice how you respond to different minerals—quartz or granite, for example, as opposed to limestone or rough conglomerate. The wooded banks of the Fairy Glen, Conwy Valley, Wales, are covered with an impressive amount of white quartz. Imagine masses of quartz crystals vibrating, amplifying the energy of the rushing water that pummels the rock-lined riverbed of the glen. Perhaps that accounts for the “fairy” in Fairy Glen.

Sometimes the sheer mass of stone is impressive. The Great Pyramid of Giza contains a huge quantity of limestone: 2,300,000 building blocks, weighing an average of 2.5 tons each and some as much as 16 tons. The massive walls of the ancient, Pre-Incan Peruvian city of Cusco are composed of carved limestone boulders perfectly fitted together without any spaces in-between—and without mortar. The largest boulder weighs 70 tons.

Sometimes ancient sites have been preserved under a layer of earth and rocks, protecting the interior structures and their decorative carvings. In Gavrinis Passage Tomb, Brittany, and Cairn T, Loughcrew, Ireland, for example, the orthostats (large upright stones that form the interior passageways and chambers) are covered with enigmatic designs. They are as sharp and clear as when they were first inscribed, many thousands of years ago. The interior stone frameworks of Pentre Ifan, Pembrokeshire, and Poulnabrone Dolmen, the Burren, Wales, on the other hand, were long ago exposed, leaving only the “bare bones,” much like a skeleton stripped of flesh.

Although dolmens are usually referred to as burial mounds and passage graves because human remains are often found within, we believe this is a misnomer. It’s like calling Westminster Cathedral a grave, just because people are buried there. Many dolmens were used for ceremony and ritual—and, depending on their construction and location, for activating or stabilizing telluric energies for the benefit of the community.

A number of researchers report strange electro-magnetic phenomena and higher-than-background levels of radiation at megalithic sites. Dowsers often discover underground lines of energy or water flowing beneath the stones. Psychics may experience strange guardian-like figures or shadowy reenactments of ancient rites. Modern researchers have discovered that many chambers appear to have a particular resonance that enhances the sound of the voice and drumming, making the sound stronger and more mysterious.

The enigmatic stones reveal and hide their purpose with the changing of the day the turning of the seasons. Spend time walking around a stone circle, sensing the stones; then choose one—or be chosen by one. When you find a stone that calls to you, draw near, breathing slowly, contemplating “the slow breath of stone.” Perhaps sing to it, or hum, or chant, and see if it replies. See what you discover as the minerals in your bones and skin and hair respond to the minerals that make up these silent monoliths. Take your time. Slow down. They’ve been there for millennia. They don’t divulge their secrets quickly—and never to the casual tourist.

Temples and Other Powerful Places

Human-constructed sacred sites are often built over ancient powerful places, sanctified by millennia of use. For example, Chartres Cathedral, a stunning Gothic construction located 50 miles southwest of Paris, was built over an ancient Druid site and holy well. Many temples are located on underground telluric lines (water or fault lines) to take advantage of these energies. The Black Madonna in the Sanctuary of the Virgin of Núria in Catalonia was carefully placed over the crossing of underground water and fire lines to take advantage of the “energetic steam” they generate.

This discussion of types of powerful places would be incomplete without mentioning battlefields (Little Big Horn, Gettysburg, the Sommé), scenes of great cruelty (Auschwitz, anyone?), places of great courage (Anne Frank House in Amsterdam), certain sports arenas (Barça stadium in Barcelona, Yankee Stadium in New York), and locations associated with iconic heroes and musicians (Elvis Presley’s Graceland, for example).

These places are powerful because of what happened there and what they stand for. Our intense emotional associations have imbued them with palpable energy. These associations are often contradictory.

Note: Most of the locations mentioned in this post are described in much more detail in our Powerful Places guidebook series.